PHOTO BY: John Malmin / Los Angeles Times

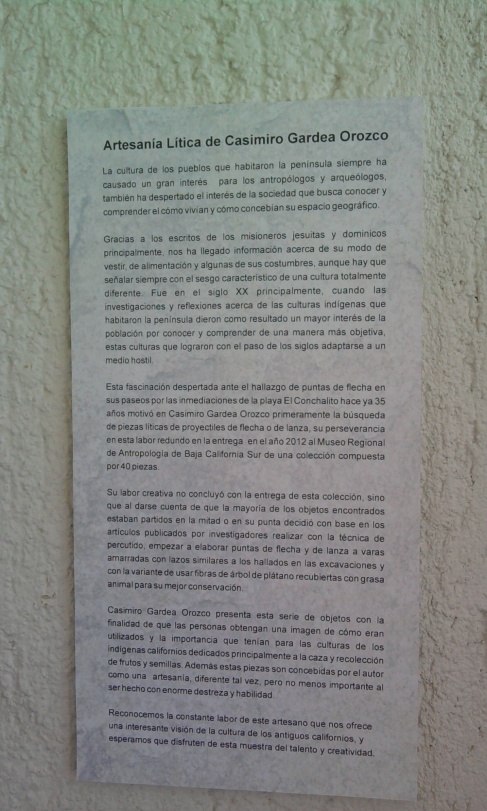

Ciclon Liza – Hurricane Liza devastates La Paz – fotos tomadas el 2 de octubre de 1976 y publicada en Los Angeles Times.

DA UN CLICK EN LAS IMAGENES PARA VER MAS GRANDEHurricane Liza devastates La Paz

Oct. 2, 1976: Area of La Paz shantytown flattened by wall of water and mud during Hurricane Liza.Around midnight on Sept. 30, 1976, Category 4 Hurricane Liza slammed into La Paz in Baja California Sur, Mexico.

Staff writer Patt Morrison reported in the Oct. 3, 1976, Los Angeles Times:

LA PAZ, Mex.––Only 24 hours after Hurricane Liza stormed through the dirt streets of the city, La Paz was burying its dead and beginning to rebuild itself.

By Saturday, rescue crews digging under mud-buried cars and rain-torn shacks had found hundreds of bodies, bringing the death toll to more than 650, and one government official said he feared it would rise to 1,000.

Saturday, La Paz was a city without adequate fresh water or gasoline, without electricity or telephones, and the first wave of relief–medicines, food, shelters–had still not shaken the city out of its shock.

The floodwater that tore through three of the Baja California city’s poor communities near midnight Thursday wiped out entire neighborhoods of flimsy cardboard, palm fond and tarpaper shacks, built in a wide, dry riverbed that had not run for years, below a low earthen dam that had withstood the weather before.

But the estimated 6 inches of rainfall that rolled off hillsides and made rivers where there had been none broke through the Porvenir (“future”) dam and swept through the shantytown, leaving thousands homeless and obliterating any trace of the settlement…

More than 400 died in La Paz, and 20,000 were left homeless. Hurricane Liza is considered the worse natural disaster to hit Baja California Sur.

These three photos by retired staff photographer John Malmin were published Oct. 3, 1976. The photo above was Page 1 lead art.

Oct. 2, 1976: Car rests on top of second in aftermath of Hurricane Liza

that lashed La Paz, Mexico. Credit: John Malmin / Los Angeles Times

Oct. 2, 1976: Young man hangs his head in La Paz street outside federal

housing project that was extensively damaged by Hurricane Liza.

Credit: John Malmin / Los Angeles Times

El Ciclón Liza enlutó miles de hogares en La Paz B.C.S. . . . . . . . . . . el dia 30 de Septiembre de 1976 hace 38 años

El ciclón Liza enlutó miles de hogares en La Paz Baja California Sur en 1976.

La noche del 30 de septiembre de 1976 el ciclón Liza de categoría 4 golpeó a La Paz, hubiera sido un ciclón mas pero el gobierno estatal había mal construido una represa que llevaba el nombre del “Cajoncito” que no soportó el caudal y literalmente reventó, muchas familias recién llegadas habían asentado sus viviendas en los cursos de los arroyos secos, “El Cajoncito” fue uno de esos lechos de arroyos que fueron poblados por razones políticas, el arroyo entra a la ciudad por un costado del cerro Atravesado justo donde termina la calle 5 de Mayo y atraviesa toda la zona nueva de camino al mar, pasa al costado del centro comercial ubicado en Forjadores y Colosio, mismo centro donde están ubicados los cines, se dice que cuando estaban excavando para construir ese centro comercial aparecieron muchos esqueletos que pertenecían a desaparecidos de cuando se desbordó el arroyo.

En su tiempo el gobierno estatal reconoció 500 y pico de muertes cifra que mas o menos coincide con el número de cadáveres que fueron identificados, los muertos fueron llevados al viejo estadio de béisbol para su identificación y después fueron sepultados en inmensas fosas comunes al fondo del panteón de los sanjuanes. Solo algunos pocos descansan en tumbas familiares.

La imagen muestra algo que parece ser una jardinera, no se engañe es una fosa común de las seis que existen y cada una mide aproximadamente 100 metros de largo, ahí descansan los restos de las víctimas que pudieron recibir cristiana sepultura . . . muchos quedaron sepultados por el lodo a lo largo del arroyo y otros muchos fueron a dar al mar, algunos fueron sacados con redes de la bahia, otros de entre los manglares de Paz, hasta se llego a comentar que algunos llegaron hasta las islas cercanas y aun en este tiempo han encontrado algunos en las nuevas construcciones que se han estado haciendo en las partes cercanas a donde llego el cause del arroyo.

Nunca se sabrá cuántas personas fallecieron la noche del 30 de septiembre de 1976. El periodista e investigador Elino Villanueva González en su libro “El Ciclón Liza” editado por la UABCS cita entre 2,000 y 5,000 el número de víctimas.

COLONIA INFONAVIT DONDE QUEDARON

MUCHOS CUERPOS ENTRE LOS ESCOBROS

EL AGUA NO RESPETO LAS CASAS

BIEN CONSTRUIDAS MUCHO MENOS

A LAS CASAS DE CARTON Y MADERA.

COL. INFONAVIT EN 1976 DESPUES

DEL CICLON LIZA

DENTRO DE ESTA CAMIONETA

SE ENCONTRO A UNA FAMILIA COMPLETA

JOVEN DE 16 AÑOS ENCONTRADO ENTRE LAS RAMAS,

Y ESCOMBROS ARRASTRADOS POR LA CORRIENTE

JOVEN SORPRENDIDA DENTRO DE SU CASA

MUJER EMBARAZADA QUE MURIO DENTRO DE CASA

PERRO LLORA A SU AMO MUERTO

MIEMBROS DEL EJERCITO MEXICANO

RECUPERANDO CUERPOS

AUTOS ARRASTRADOS POR LA CORRIENTE

EL ARROYO DEL CAJONCITO CAUSANTE DE ESTA

TRAGEDIA Y DEL BORDO MAL CONSTRUIDO

LEA MI HISTORIA

“YO SOBREVIVI AL CICLON LIZA”

Mi historia comienza el 30 de Septiembre de 1976

recuerdo que ese dia me levante muy tamprano para irme a trabajar con mi

padrastro con quien estaba trabajando practicamente desde que habia

llegado a esta ciudad, ya tenia un año trabajando con el en la

construccion, yo llegue a La Paz, en el mes de agosto del 1975, en el

barco que se hundio frente a la Isla del Espiritu Santo “El Salvatierra”

que segun lei en algun libro estaba construido con cemento y metal.

Recuerdo que ese dia me fui con mi padrastro a terminar el emplastado de unos locales que habiamos construido frente al cuartel militar, el me dejo ahí junto con otro Señor que creo que se llamaba Valentin, ya estabamos por acabar cuando el me dijo que el dueño decia que dejaramos de trabajar y que nos fueramos para nuestras casas por que el Ciclon si iba a llegar, asi lo hicimos limpiamos todas las herramientas y las guardamos ya para esto creo yo que eran como las 10:30 de la mañana, terminamos nos despedimos y como el andaba en bicicleta se fue en ella y yo acostumbrado a caminar me fui caminando.

Pues bien no habia caminado ni cinco cuadras cuando empezaron a caer las primeras gotas de agua, me apresure a llegar a la casa pero para cuando llegue ya iba todo mojado, sin cambiarrne de ropa, llegue y salude a mi mama que estaba atendiendo al niño mas chico, y le dije que el ciclón ya iba a llegar y me puse a tapar las ventanas y la puerta lo mejor que pude, la puerta le clave una cobija gruesa y le puse unas piedras grandes y unos blocks para que soportaran las fuerza del viento que para ese entonces ya eran bien fuertes y tenia que acomodarla a cada rato, asi estuvimos como hasta las 3 o 4 de la tarde no recuerdo la hora creo que fue a esa hora que se calmo un poco todo y sali a acomodar las cosas.

Mi padrastro llego en una camioneta aprovechando ese momento de calma para llevarnos a un refugio que estaba ubicado en el cuartel pero en eso todo empezo de nuevo lluvia y viento y cada vez mas fuerte que antes, sin tomar nada de la casa unicamente unas cobijas para cubrir a los niños nos subimos y ahi vamos por las calles llenas de arroyos que no se podia circular ni ver por los parabrisas ya que no se daban abasto de tanta agua que caia, habia momentos que no se veia por donde ibamos, nos atascamos muchas veces hasta que un techo de una casa cayo frente a la camioneta y entonces se decidio que mejor nos regresariamos a la casa y asi lo hicimos.

nos regresamos atascandonos en el lodo y los arroyos, ademas de las laminas que se hacian rollito y pegaban contra la camioneta y objetos que hasta parecian piedras grandes las que golpeaban los costados de la camioneta, varias veces puedo decir que cargamos la camioneta para sacarla de los arroyos que cada vez parecian mas grandes hasta que por fin llegamos creo yo que pasamos unas dos horas en regresar ya serian como las seis cuando antes de bajarnos de la camioneta el compadre de mi mama fue y nos dijo que nos fueramos con ellos porque su casa era de material y tenia techo de colado, practicamente era un buen refugio para nosotros y las otras 4 familias que ya estaban alli,

nos sentimos comodos tomando cafe y platicando, estabamos seguros en esa casa, se sentia un buen animo y todo lo que habiamos pasado ya era cosa del pasado, ya se platicaba de como eran los lugares de donde cada uno venia porque todos veniamos de otros estados a trabajar aqui ya que creiamos que aqui era como ir a estados unidos a ganar dolares, porque era zona fronteriza y habia mucho turismo y todo se pagaba y compraba en dolares asi transcurrieron unas 3 horas mas hasta que escuchamos un ruido muy diferente al ruido del viento y el agua que azotaban las paredes y el techo se escucho un ruido sordo y un pequeño temblor que poco a poco se fue acercando a nosotros hasta que un muchacho como de mi edad dijo que ya era hora de regresarse a su casa porque el habia ido unicamente a acompañarnos un rato

y asi lo hizo salio por la puerta pero no tardo ni unos diez minutos cuando volvio a tocar la puerta diciendo que no habia podido pasar el arroyo que ya la corriente estaba muy fuerte ya para entonces el agua se estaba metiendo por la abajo de las puertas que habian puesto cobijas para tratar de detenerla pero era inutil hasta que oimos como la pared de un cuarto que se encontraba vacio cedio ante la fuerza del agua y se vino abajo, escuchamos como el agua golpeba la pared del segundo cuarto donde ya lo habiamos dejado cerrando las puertas y atracandolas con los muebles tratando de detener la fuerza del agua del otro cuarto que habiamos dejado

hasta que sentimos que no iba aguantar entonces nos dijo el señor que nos metieramos en la casa rodante que estaba afuera y asi los hicimos todos no metimos en el camper al parecer todos los escombros y madera de las casas que la corriente ya habia destruido de alguna forma habian formado una isla que nos protegia como un barrera donde chocaba el agua y la desviaba por los lados hasta que llego un momento que sentimos como las piedras y escombros de las paredes que ya habia tumbando y que arrastaba la corriente del agua golpeaban abajo de nosotros, uno de los señores que estaba con nostros dijo que escuchaba un niño que lloraba abajo de camper y salio junto con mi padrastro a buscarlo fue entonces cuando la ultima pared cedio a la fuerza del agua cayendo sobre el camper y volcandolo, escuchamos como el sr. que habia salido ha buscar el niño era aplastado por el camper y por logica pensamos que a mi padrastro tambien le habia pasado lo mismo,

pero despues el me platico unos dias despues como el se salvo cuando el camper se volteo el agua provoco una gran ola que lo encaramo arriba de un cardon que estaba enfrente de nosotros y alli estuvo agarrado varias horas hasta que el agua del arroyo bajo y lo pudieron bajar de alli y me mostro como aun tenia una gran cantidad de espinas encajadas dentro del cuerpo que estaban esperando los doctores que le cuerpo las arrojara solo, me menciono que el vio todo lo que paso despues de eso y observo como todos los que ibamos sacando del camper el agua se los llevada hasta vio como el otro muchacho y yo quedamos unicamente arriba del camper hasta que el agua lo hizo flotar y como una ola grande nos cubrio y nos arrojo a la corriente, bien regreso hasta el momento en que el camper volco, en ese momento lo primero que se nos ocurrio a todos fue encomendarnos a Dios y sacar a las mujeres y a los niños primero y asi lo hicimos sacamos a cada uno a empujones y como pudimos los subimos por la puerta que habia quedado en el techo pero asi como iban saliendo asi tambien el agua se los llevaba ya que no habia de donde sostenerse, para cuando nos toco salir a nosotros primero por intuicion ayude primero a salir al muchacho porque el era mas grande y alcanzaba mas bien lo alto de la puerta y no lo pense hasta despues de muchos años que mi logica fue la correcta porque como yo pesaba menos fue para el mas facil levantarme y ayudarme a subir al camper alli estuvimos aferrados a la puerta del camper para donde voltearamos a ver habia agua podiamos ver el reflejo del agua como si estuvieramos en el mar no podiamos mirar donde empezaba o donde terminaba era un mar de agua, a pesar de estar obscuro se podian ver las siluetas de las cosas como si hubiera luz de luna, creo que alli permanecimos como unos veinte minutos hasta que sentimos como nuestra pequeña isla se empezo a mover y a flotar como cuando la corriente trae mas agua,

en ese momento escuche el llanto de un bebe y lo alcance a distinguir entre las tablas y sin pensarlo baje por el, el muchacho me ayudo a subir otra vez recuerdo que cuando pisaba las tablas sentia como estas ya estaban flotando en el agua porque senti como si estuviera pisando sobre un colchon y siempre con el temor de hundirme todo lo hice en un tiempo de cuestion de segundos que se coordinaron con los del muchacho y como si cada quien supiera lo que tenia que hacer lo hicimos brinque tome y subi del braso que el me tendio sin pensarlo por la cuestion del momento si se soltaba caia al agua y el deber humano de ayudarme a intentar de salvar a ese niño aunque fue un intento vano ya que ni bien termine de agarrame con una mano a la puerta del camper cuando una ola grande de agua nos cubrio totalmente y cuando ya paso no tenia ni al niño que era mi hermanito, ni al muchacho a los dos se los habia llevado la corriente, ya antes de eso le habia dicho al muchacho que tomara una tabla de entre los escombros para usarla como flotador, y como el no se decidia a hacerlo yo le di una antes de bajar por el niño no se si por ayudarme la haya soltado o que paso, despues de eso ya me senti solo y hasta que otra ola paso por encima de mi y ya no pude sosterme senti como las yemas de mis dedos se desprendia en un intento fallido de no soltarme pero de pronto ya estaba en el agua sambullendome, saliendo, sambullendome y saliendo asi estuve hasta que no supe como logre asirme a un pedazo de barrote de madera que paso cerca de mi, con eso logre mantenerme un poco mas de tiempo a flote hasta que en la penumbra empece a distinguir la punta de unos postes de cerco de puas, dentro de mi pensaba que si el agua me hacia pasar por ahi ese seria mi final a como me acercaba trataba de mantenerme en una posicion lo mas horizontal que pudiera para tratar de pasar como si fuera una tabla por entre los alambres pero cuando ya pasaba , pensaba por lo menos me libre de una mas,

una de la veces mire los postes de alta tension y miraba como la corriente me llevaba hacia ellos, en una ocasion me acerco tanto la corriente que intente subirme a uno pero frente a ellos se formaba una bolsa de aire que no me permitio ni siquiera estrellarme con la base de cemento de estos, asi segui en algunas ocasiones que iba flotando ya sin la madera sentia como las grandes piedras que el agua llevaba arrastrando pasaban por debajo de mi sin tocarme senti como me rosaban las piernas pero ninguna me toco gracias a Dios. hubo ocasiones en que le agua era tan bajita que intente pararme y algunas veces que lograba hacerlo, la corriente del agua hacia que la arena desapareciera debajo de mis plantas de los pies y volviera a caer lo intente muchas veces pero no podia mantenerme de pie hasta que ya no volvi a intentarlo,

deje que el agua me chocara la espalda y asi me impulsaba a mucha velocidad durante grandes tramos hasta que volvia a caer en partes profundas y otra vez a sambullirme y tratar de mantenerme a flote en las aguas turbulentas de este mar de agua corriente, recuerdo que en cuando el agua me empujaba dandome en la espalda senti el piso mas duro que la arena donde ya tenia un rato flotando practicamente sentado y asi iba acercandome aun sitio donde alcance a distinguir un ruido muy diferente al de el agua corriendo escuchaba un gran caida de agua, y mi mente inmediatamente se imagino que adelante habia una cascada porque en chihuahua ya habia escuchado varias veces ese ruido, asi como mi temor de quedar enredado en un cerco de alambre se debia a que ya habia visto en chihuahua como las vacas morian cuando eran arrastradas por los arroyos y quedaban atoradas entre los alambres y ahi me imaginaba que quedaria si me atrapara algun cerco, asi que al escuchar el agua borbotear a pocos metros donde irremediablemente caeria y tal vez perderia la conciencia con la caida o terminaria con golpes graves y huesos rotos ese era mi miedo en ese momento,

pero no podia hacer nada asi que me prepare mentalmente para recibir lo que pasara y cuando ya iba de caida de pronto senti un fuerte frenon en la caida quede cubierto por el agua por del lado contrario a la corriente mis piernas recibian los chorros de agua asi que no podia enderezarme para tomar aire y asi estuve unos momentos hasta que por inercia trate de safarme de los que me tenia detenido y alcance a agarrame en un momento que pude tomar aire y doblarme en una lucha constante contra la corriente del arroyo y asirme de de la raiz de un pequeño arbol que tambien luchaba contra la corriente y que habia atrapado parte de los hilachos que aun conservada del pantalon estos se habian enredado en su raiz evitando que yo siguiera en el curso del arroyo asi que como pude busque la forma de enderesarme hasta que lo logre y pude sentir nuevamente piso firme aunque sentia como este se estaba debilitando tanto por mi peso como el del agua que desgastaba rapidamente esa pequeña isla asi que me agarre del pequeño pero resistente troco del arbolito y ahi permaneci un rato, mirando entre los reflejos del agua como una gran cantidad de gente pasaba cerca de mi y caian en donde yo deberia de haber caido en algunas ocasiones alcance a ver como algunos estiraban los brasos para que les ayudara pero en mi situacion no podia hacer nada ya que quedaban fuera de mi alcance y tambien porque yo estaba dentro del agua con el agua a la altura del pecho sin poderme mover, recuerdo que poco a poco empece a distinguir los sonidos diferentes al agua cayendo y corriendo hasta que distingui que alguen me gritaba desde las casas de infonavit que aguantara que ya me iban a ayudar, busque de donde me gritaban y localice a una persona que apuntaba la luz de su lampara hacia donde yo estaba y sentia que este me gritaba a mi, entonces reaccione y le grite pidiendo sus ayuda pero creo que el no me escuchaba porque tambien dirigia la luz hacia una gran pared que se encontraba frente a mi pasando la calle hoy forjadores y miraba como habia mucha gente protegiendose con un edificio de pared blanca y se distinguian las siluetas de la gente moviendose de una lado a otro pero por ambos lados salia el arroyo y no los dejaba moverse, despues volvia nuevamente conmigo y ya le escuchaba mas clarito que me decia que ya iban por mi, pero no miraba que el se acercara a donde yo estaba, cuando de pronto escuche que a unos 30 metros alguien me decia yo te voy a ayudar aguanta un poco mas . . . entonces ya distingui la silueta de alguine que se acercaba agarrandose de unos juegos que parecian unos columpios o resbaladillas hasta que se aproximo lo suficiente para estirar su brazo y decirme que lo sujetara fuerte y que no me soltara y asi lo hice el dio un tiron y yo me solte de arbolito y me acerque a el que me dijo camina cerca y detras de mi y pisa donde yo piso y asi lo hice lo segui hasta que logramos llegar hasta la banqueta que esta enfrente de la colonia infonavit donde ahora hay un muro de piedra y empezamos a caminar por ahi hacia la calle sinaloa, recuerdo que mientras ibamos llegando a la calle jalisco nos encontramas a un sr. dentro de una jaula que ponian para proteger las tomas de agua y le dijimos que se saliera de alli y se fuera con nosotros porque si el agua volvia a subir el se ahogaria estando ahi adentro pero el no quiso y se metio mas dentro de esta jaula, nosotros seguimos hasta que agarramos la antigua carretera al sur caminando por la orilla de la gran fila de carros que habian quedao atrapados entre la calle sinaloa y la calle colima, todos nos miraban asombrados pero nadie se acerco ni pregunto nada sencillamente al vernos llenos de harapos, lodo, y semidesnudos se hacian a un lado para que pasaramos, tal ves fuimos los primeros que ellos miraban de los que habiamos logrado salir de las fuertes corrientes desbordadas y furiosas de un caudal de agua incontenible tal ves hasta el dia siguiente se enteraron de la magnitud de la tragedia que La ciudad de La Paz acaba de vivir, tal ves en esos momentos mucha gente aun se encontraba flotando viva o muerta en la bahia de la paz, caminamos hasta llegar a la calle sinaloa esquina con la hoy forjadores donde hicimos el intento de pasar pero no pudimos ya que la corriente era muy fuerte asi que nos sentamos pegados a la pared a esperar que bajara el nivel del agua para poder pasar, ahi estuvimos un buen rato hasta que una sra. salio de la casa que aun esta ahi y nos invito a pasar a su casa y nos dijo que en la casa ya habia mucha gente pero que podiamos quedarnos en uno de los carros y nos abrio la puerta de uno de ellos mientras fue y nos preparo un te caliente. fue cuando ya estabamos dentro del carro cuando se prendio la luz interior cuando me di cuenta que el muchacho que me habia ayudado era el mismo que estaba junto con nosotros en la casa pero no volvimos a hablar despues desde que el me dijo que lo siguiera, ya dentro del carro note que el se frotaba su mano derecha y tambien vi como su dedo menique le colgaba y lo unico que lo unia a su mano era un pedazo de piel, hasta ese momento el no se habia dado cuenta de eso, cuando la sra. nos trajo el te le pedi si tenia unas tijeras y la sra sin preguntar nada fue y me las trajo y con ellas le corte el pedazo de piel, le envolvi su dedo en un paño que encontre en el asiento y se lo puse en sus mano, el apreto sus dedo ya despues de eso me quede dormido, cuando volvi a despertar el ya no estaba, entonces sali del carro y de la casa ya el arroyo de la calle sinaloa no estaba corriendo, empece a caminar pero como a unas dos cuadras aun se escuchaba el rumor del agua del arroyo corriendo, cuando de pronto unos soldados me detuvieron y me preguntaban que estaba haciendo yo ahi que era muy peligroso por lo del el arroyo les dije que yo habia salido del el, ahi fue donde empece a ver los primeros muertos revueltos entre los escombros, tablas, madera, ramas muebles y todo lo que estaba en la orilla del arroyo, unos sacaban un brazo o una pierna de algunos se miraba su espalada la cabeza y piernas estaban dentro de la basura ya los soldados estaban separando los cuerpos tenian ya ha algunos con uniforme y al parecer estaban separando nada mas los de ellos, asi que uno de los soldados me llevo con el que tenia mayor rango que el y le comento que yo habia salido vivo del agua, el le dijo que me subiera a un jeep y que me llevara a una escuela que era un albergue y asi lo hizo me subio y me llevo a una escuela que no recuerdo cual era pero si recuerdo que por donde iba el jeep en algunas partes el agua casi le tapaba las llantas, el soldado me dejo en la escuela recomendandole a la persona que estaba a cargo que no me perdiera de vista y asi lo hiso me trajo una cobija y me acomodo en uno de los salones donde mire por la ventana como el agua corria con mucha fuerza por los costados de esta y ahi me volvi a quedar dormido hasta que ya casi amaneciendo alguien me desperto preguntandome si estaba yo herido, le enseñe mis manos y me dijo que me subiera al camion que nos llevarian al hospital para que nos checaran, subieron gente con grandes golpes en la cabeza, algunos con las piernas y brazos muy golpeados otros aun inconcientes y asi nos fuimos, llegamos al hospital y alli permaneci varias horas hasta que un doctor me pregunto que si que tenia le mencione que mis dedos no tenian la piel y tenia un golpe en la parte baja del estomago, me reviso y me dijo que no tenia nada, me lavo las manos con agua oxigenada, dijo que me prestaria una ropa y asi lo hiso fue y me trajo un pantalon y una camisa, alli mismo me los puse, y sali a la calle con rumbo a donde estaba nuestra casa subi por la misma calle nicolas bravo a como me acercaba a la zona afectada se empezaba a apreciar lo que el agua habia hecho, cuando llegue hasta el arroyo ya no habia agua parecia que nunca habia corrido por ahi, habia partes que estaban tan limpias que parecian que habian barrido, la arena estaba tan blanca que lastimaba la luz del sol, ya empezaba a ver nuevamente los cuerpos enterrados en la arena y a mucha gente buscando cuerpos, y marcando donde estaban, los pickups pasaban llenos de cuerpos llenos de tierra y lodo y segui caminando hasta que llegue a nuestra casa, me sorprendi porque todo estaba igual que cuando nos fuimos, la cobija estaba en sus sitio, el agua habia subido como unos 20 cms. ni siquiera llego a tocar el colchon de la cama, ahi me sente un rato a pensar en todo lo ocurrido hasta que llego mi hermano mayor y me pregunto por todos le dije que a todos se los habia llevado el agua, lloramos juntos y ya que nos calmamos decidimos ir buscar a nuestros familiares, buscamos en muchos sitios sin encontrar nada, hasta que por fin en unas canchas que estan por la calle allende ahi vimos como lavaban los cuerpos con una manguera para quitarles un poco la tierra, lodo y basura para que los familires pudieran reconocerlos mejor, ahi encontramos primeramente a mi hermano de 6 y adentro del local encontramos a mi madre abrasando al bebe, por alguna razon cuando el bebe se escapo de mis manos ella

lo recupero en el agua y ya no lo solto muriendo juntos, a mi hermana no la encontramos, mi otro hermano menor que yo, los soldados lo encontraron en el armazon del techo de una casa cerca del hotel Gran Baja, el se salvo porque un clavo muy grande le atravezo el empeine del pie atravezandolo de lado a lado y anclandolo a la estructura no permitiendo que la corriente lo llevara al mar. estuvo en tratamientos medicos y recuperacion por mas de un año, despues de eso por sugerencia y ayuda de mi hermano mayor nos internamos los tres en La Ciudad de Los Niños de La Paz, A.C. ahi estuve de aprendiz en el taller de Imprenta ayudando a los Diseñadores Graficos en la limpieza y encargos que ellos necesitaran y observando su trabajo y ayudandoles con los encabezados de los periodicos y revistas que se publicaban en ese tiempo fui aprendiendo poco a poco a dibujar y a diseñar, papeleria para oficinas, escuelas, dependencias de gobierno, revistas, peridicos carteles, volantes, me pefeccione en el uso de las encabezadoras Strip Printer, que era una maquina de papel fotografico que se tenia que revelar en grandes tira en un cuarto obscuro, tambien perfeccione mi tecnica de hacer encabezados en la maquina Varityper que era una encabezadora que se utilizaban unos discos grandes que imprimian la letra que uno seleccionaba en una cinta adhesiva que despues se cortaba y se pegaba donde se queria, asi estuve como unos dos años hasta que por coincidencia uno de los Diseñadores enfermo y lo incapacitaron por varios meses y se me pregunto que si podia tomar su lugar en lo que el regresaba acepte y resulto que hice bien mi trabajo que a partir de alli me gane mi lugar como diseñador y dibujante, poco despues la secretaria que llenaba los formatos con una maquina que usaba unas bolitas de cromadas de platino LA IBM se incapacito por embarazo y no se encontro quien la supliera y como tambien habia visto como los llenaba tambien tome su lugar llenando los formatos y asi fui superandome en este trabajo que desde 1978 hasta la fecha he desempeñado y creo que lo sigo haciendo bien no tengo titulo de Diseñador Grafico pero tengo el gusto de haber asesorado a varios de ellos, incluso unos de mis hijos es Lic. en Diseño Grafico egresado de la Universidad Mundial, tome varios cursos en la Universidad Autonoma de Baja California Sur, cuando aun esta Carrera no existia en nuestro estado, ademas de adquirir toda la informacion que podia sobre temas de artes grafico, diseño y fotografia, he manejado el CORELDRAW desde el No. 1 hasta el 14 que es el que esta actualmente. esa ha sido mi escuela ademas del trabajo diario..

ESTE ES LA TRAYECTORIA QUE RECORRI DENTRO

DEL ARROYO, PRACTICAMENTE LO ATRAVESE

DE LADO A LADO

ESTA HISTORIA SE LA DEDICO A TODOS LOS QUE DE ALGUNA MANERA

SON SOBREVIVIENTES DE ESTE CICLON LIZA QUE MARCO LA VIDA

DE MUCHOS DE NOSOTROS, PERO TAMBIEN NOS DEJO UNA GRAN

EXPERIENCIA A TODOS LOS SUDCALIFORNIANOS QUE AUN QUEDAMOS

DE ESA EPOCA EN TODO LO QUE A CICLONES Y A UNIDAD FRATERNAL

SE REFIERE..

LOS PAISES DEL MUNDO APOYARON EN GRAN MANERA A

TODOS LOS QUE RESULTAMOS DAMNIFICADOS,

EN LA COLONIA 8 DE OCTUBRE AUN QUEDAN CASAS

ORIGINALES PROTOTIPO ANTISISMICAS QUE NO

RECUERDO QUE PAIS FUE EL QUE LAS DONO,

PERO GRACIAS A ELLOS MUCHOS AUN VIVEN EN ELLAS.

arroyo el cajoncito

Sep 30th is the 37th Anniversary of the Arrival of Hurricane Liza; the Worse Day In La Paz History September 30th, 1976 began like most other late summer days in La Paz, hot and humid—though perhaps a bit more overcast than usual.

The port was abuzz with the news that a tropical cyclone was in thevicinity, but most Paceños didn’t get overly concerned about such reports since more often than not these disturbances passed harmlessly by.

Besides, Hurricane Liza—if it came at all—wasn’t scheduled to brush past the city until the pre-dawn hours of the following morning. The city’s schools convened classes on schedule as the rest of the town’s people went about their normal.

Thursday morning routine. The state governor was so unconcerned about the weather that he boarded an early plane for Mexicali to attend a political function being hosted later that morning in the capital of the northern half of the peninsula.

But by 10:30 a steady drizzle blanketed the city and the wind picked up. People began scurrying home to get out of the weather. As three o’clock rolled around the skies were dark and menacing as howling gusts accompanied a relentless downpour soaking the region. By 7 p.m. it was apparent to most of the city’s residents that this storm was different from most.

Liza had brought some serious hydraulic action with her.

Streets that had once been arroyos became raging rivers as the torrential rains made their way through the city to the Bay of La Paz. Even the oldest Paceños couldn’t remember ever having seen the water rise as high as it did that September evening. Homes near arroyos throughout town flooded for the first time and vehicles were swept away when their drivers challenged the currents.

Then things got really bad.

Sometime between 8 and 9 p.m., a loud crackling sound was heard throughout the city.

Most residents I talked to described it as sounding like a loud explosion.

One person said it reminded him of when they blasted the road through to Pichilingue in the early 1960s.

The sound was caused by the rupturing of a dike meant to protect the city’s eastern flank from

the periodic floodwaters that come out of the Arroyo El Cajoncito.

Satellite Image Of Arroyo El Cajoncito and surrounding area

Arroyo El Cajoncito is actually the convergence of several major arroyos that drain a sizable area of the sierras east of town.

The arroyo gets its name from a rocky “bottleneck” that forms a narrow gateway where the arroyo leaves the sierras that the waters must pass through. Once the waters clear the bottleneck at El Cajoncito, they make their way to the sea through five large arroyos that flow over the alluvial plain that La Paz is built on (in fact, they are responsible for bringing from the nearby hills the material the city’s built on). Or at least, that is how things worked until the mid-1960s, before government officials built a 10-meter high dike meant to block the natural paths the old waterways took through the city and divert their flows to the east and south of town to the Arroyo El Piojo (this arroyo flows past the UABCS).

But what the planners of the project hadn’t counted on was the severity of the tromba (localized storm characterized by a heavy downpour) that unloaded over the region east of the state capital on that fateful day. A rare combination of meteorological factors converged over the sierras east of La Paz and reportedly dropped 800 highly-localized millimeters (over two and a half feet) of rain in just over an hour.

Initially, the bottleneck at El Cajoncito Arroyo and a low area to the north of it known as Llano La Laguna worked in tandem to minimize the hydraulic force applied to the outer wall of the recently-built dike. But once the Llano La Laguna was full even as the floodwaters continued to roar out of the Cajoncito Arroyo, that changed. Tragically, a section at the southern end of the dike gave way and allowed most of the waters flowing out of Arroyo El Cajoncito to sweep through the southern section of the city.

The bottleneck at Arroyo El Cajoncito

An old (1940s) irrigation project at the bottleneck

The result of this unfortunate miscalculation by authorities was that in about 10 hours the aguas broncas (raging waters) from the arroyo wiped out about a quarter of the city of La Paz, an area that included some 30 colonias. Concrete houses in the path of the flood were

simply washed away, leaving no trace of their ever having existed.

When the houses were able to withstand the force of the water, often the people inside drowned. Residents could only watch helplessly from the banks as individuals and cars—some with whole families in them—floated by, most to a certain death.

While the real death toll will never be known–official sources place the number of dead and disappeared in the mid-500s–some have estimated that more than 10,000 people lost their lives that night, amounting to about 12 percent of the city’s population.

At the time, it was the deadliest natural disaster in the nation’s history, a mark that was surpassed in 1985 when an earthquake shook apart Mexico City. Compounding the problem of an accurate count of the deceased (if the Mexican government had really wanted one) was the fact that most of those who died were recent arrivals to the city, many of them residing in “irregular communities.”

Few natives lost their lives. I’ve lots of Paceño friends, most of them from the city’s old families and not one of them lost a relative in the disaster. The reason most likely is because they all lived near the city’s center and not in the southeastern corner that was devastated.

Although Liza was the wettest storm to strike the city in over a century, a post-disaster review of the events leading up to the catastrophe indicated that the calamity was far from unpredictable. In fact, Sebastian Diaz Encinas, a hydraulic engineer who had been involved in flood control issues in the region since the 1940s, had been sounding the alarm and warning of just such a thing happening for several years before the arrival of Liza, but nobody was listening.

Events Leading Up to the Tragedy

Anyone acquainted with the geography of La Paz knows that heavy rains can make some of the city’s streets impassible at times. Because of its location on the delta of an alluvial plain formed by arroyos that dewater the nearby sierras during rains, sections of La Paz have always been prone to flooding whenever storms passed through the region.

The city’s total lack of storm drains to help purge its streets only aggravates the problem.

Prior to 1960 the town was small enough that there was still plenty of undeveloped “safe land” so people didn’t build in arroyos.

When floods came, they were little more than an inconvenience for most of the city’s residents, although there have always been the occasional innocents who have paid with their lives for not recognizing the danger of the swift currents that are sometimes unleashed from the sierras.

n the 1960s the pace of the city’s growth picked up.

The agricultural colonies that were established in the 1940s and 50s in the Santo Domino Valley, Los Planes, Todo Santos and around La Paz began to bear fruit, attracting more people to the southern peninsula. Many of these recent arrivals chose.

La Paz as a place to settle once they had fulfilled their agricultural contracts. When ferry service connected the territorial capital with the mainland in 1964, the peninsula’s duty-free status also stimulated the city’s development as an army of petty capitalists invaded the city’s main business district shortly after each ferry’s arrival at Pichilingue. Some of them undoubtedly stayed on.

The completion of the Transpeninsular Highway in 1973 brought even more people to the southern peninsula in search of better economic opportunities.

It took 140 years for La Paz to reach a population of 17,000 people, something the city achieved in 1950. It took only twenty years to triple that number, so that by 1970 more than 51,500 individual called the city “home.” By then, the only lands available “in town” were in the flood zones. But the city continued to expand anyway.

Irresponsible or corrupt public officials looked the other way as waterways were invaded and often filled in with garbage and other debris by people who knew nothing of the dangers of flash floods in desert environments. Rather than uprooting the informa communities that sprung up in dangerous areas and having to find more suitable (and expensive) lands for them, officials decided it made more sense to incorporate them into the system Nwhere they were, providing the new colonias with public services and, of course, taxing them. No sooner did one paracaidista (literally, “parachutist” which means “squatter” in this context) community get legal recognition, another would form a little further out.

In the late 1960s territorial officials decided to protect the new colonies from the occasional floodwaters that come out of El Cajoncito Arroyo by building the now-infamous first bordo de contencion (containment boundary). The plan called for building a three kilometer earthen dike across the gap separating San Juan Hill and Atravesado Hill (these are the two principal hills one sees behind the city when looking at La Paz from a boat or from the Mogote). The idea was a good one, since—if done property—it would effectively divert the waters coming out of the sierras east of town around the city to the big arroyo that passes next to the university south of La Paz (Arroyo El Piojito).

Unfortunately, federal officials chose to fund the cheapest of the three proposals submitted. Factor in the usual graft and corruption that accompanies these types of projects in Mexico and what was finally built was a 10-meter-high sand barrier with a rock surface facing the arroyo, cement was used sparingly in its construction.

The project was completed to great fanfare in 1970 or so.

The bordo provided a sense of security and became the de facto eastern limit of town as the lands right up to it were soon urbanized.

I’m not aware if the bordo was ever put to the test by a hurricane in the few years between its completion and the arrival of Hurricane Liza.

In normal conditions, the waters that run down the arroyo don’t jump the steep sand banks that are characteristic of it through most of its passage east of town, so waters from Cajoncito Arroyo wouldn’t ordinarily have been running along the bordo. But what happened with Liza was that an inordinate amount of water fell over a very short period of time, water which apparently backed up behind the bordo while making its way behind Atravesado Hill to Piojito Arroyo.

Once the section of the bordo gave way, the arroyo reclaimed its old waterways to the sea through the southeastern sector of the city.

It was a “had to be there” moment to fully appreciate what had happened.

Most of the city’s residents didn’t realize the cause of the “explosion” heard that early evening and word didn’t filter back to the rest of the city of the horror that had visited the eastern and southern sections of town until the next morning.

While my family was long gone when Liza devastated La Paz,

I had several friends who were volunteers at the La Paz offices of the Red Cross in 1976. All of them were called in to begin hauling bodies in the pre-dawn hours of Oct. 1st. Initially, the corpses were taken to the Salvatierra Hospital (then on Bravo Street), but as this facility was soon overwhelmed, the dead were taken to the Cancha Manuel Gomez Jimenez on Bravo Street and to the GUM Gym on 5 de Febrero (right on the very edge of the arroyo) and several other locations around town.

The initial idea was to give next-of-kin a chance to claim their relatives.

But as the magnitude of the devastation was realized, government officials decided that the original plan was impractical as bodies quickly began to decompose in the tropical heat. Two backhoes were ordered to the Sanjuanes Cementary where they dug five trenches, each some 70 yards long. The dead were wrapped in make-shift sheets (they bought bolts of cloth from local stores to make them) and dumped one body on top of another in common graves. Six tons of cal (lime) were used to cover the dead to help contain the spread of disease.

It didn’t take more than a few days for public officials to call off the search for bodies, deciding that the arroyo was as good a place as any to be buried. Today one still occasionally hears of a construction site finding human remains in the sections of the city that were flooded.

In doing the research for this essay, I visited the site where the old dike was located, I rode my bike down the arroyo that overflowed with death on that September night and also rode to the top of

Atravesado Hill to survey the area where the nightmare began.

I studied the new fortifications that protect the city from the Cajoncito Arroyo today.

simply washed away, leaving no trace of their ever having existed.

When the houses were able to withstand the force of the water, often the people inside drowned. Residents could only watch helplessly from the banks as individuals and cars—some with whole families in them—floated by, most to a certain death.

While the real death toll will never be known–official sources place the number of dead and disappeared in the mid-500s–some have estimated that more than 10,000 people lost their lives that night, amounting to about 12 percent of the city’s population.

At the time, it was the deadliest natural disaster in the nation’s history, a mark that was surpassed in 1985 when an earthquake shook apart Mexico City. Compounding the problem of an accurate count of the deceased (if the Mexican government had really wanted one) was the fact that most of those who died were recent arrivals to the city, many of them residing in “irregular communities.”

Few natives lost their lives. I’ve lots of Paceño friends, most of them from the city’s old families and not one of them lost a relative in the disaster. The reason most likely is because they all lived near the city’s center and not in the southeastern corner that was devastated.

Although Liza was the wettest storm to strike the city in over a century, a post-disaster review of the events leading up to the catastrophe indicated that the calamity was far from unpredictable. In fact, Sebastian Diaz Encinas, a hydraulic engineer who had been involved in flood control issues in the region since the 1940s, had been sounding the alarm and warning of just such a thing happening for several years before the arrival of Liza, but nobody was listening.

Events Leading Up to the Tragedy

Anyone acquainted with the geography of La Paz knows that heavy rains can make some of the city’s streets impassible at times. Because of its location on the delta of an alluvial plain formed by arroyos that dewater the nearby sierras during rains, sections of La Paz have always been prone to flooding whenever storms passed through the region.

The city’s total lack of storm drains to help purge its streets only aggravates the problem.

Prior to 1960 the town was small enough that there was still plenty of undeveloped “safe land” so people didn’t build in arroyos.

When floods came, they were little more than an inconvenience for most of the city’s residents, although there have always been the occasional innocents who have paid with their lives for not recognizing the danger of the swift currents that are sometimes unleashed from the sierras.

n the 1960s the pace of the city’s growth picked up.

The agricultural colonies that were established in the 1940s and 50s in the Santo Domino Valley, Los Planes, Todo Santos and around La Paz began to bear fruit, attracting more people to the southern peninsula. Many of these recent arrivals chose.

La Paz as a place to settle once they had fulfilled their agricultural contracts. When ferry service connected the territorial capital with the mainland in 1964, the peninsula’s duty-free status also stimulated the city’s development as an army of petty capitalists invaded the city’s main business district shortly after each ferry’s arrival at Pichilingue. Some of them undoubtedly stayed on.

The completion of the Transpeninsular Highway in 1973 brought even more people to the southern peninsula in search of better economic opportunities.

It took 140 years for La Paz to reach a population of 17,000 people, something the city achieved in 1950. It took only twenty years to triple that number, so that by 1970 more than 51,500 individual called the city “home.” By then, the only lands available “in town” were in the flood zones. But the city continued to expand anyway.

Irresponsible or corrupt public officials looked the other way as waterways were invaded and often filled in with garbage and other debris by people who knew nothing of the dangers of flash floods in desert environments. Rather than uprooting the informa communities that sprung up in dangerous areas and having to find more suitable (and expensive) lands for them, officials decided it made more sense to incorporate them into the system Nwhere they were, providing the new colonias with public services and, of course, taxing them. No sooner did one paracaidista (literally, “parachutist” which means “squatter” in this context) community get legal recognition, another would form a little further out.

In the late 1960s territorial officials decided to protect the new colonies from the occasional floodwaters that come out of El Cajoncito Arroyo by building the now-infamous first bordo de contencion (containment boundary). The plan called for building a three kilometer earthen dike across the gap separating San Juan Hill and Atravesado Hill (these are the two principal hills one sees behind the city when looking at La Paz from a boat or from the Mogote). The idea was a good one, since—if done property—it would effectively divert the waters coming out of the sierras east of town around the city to the big arroyo that passes next to the university south of La Paz (Arroyo El Piojito).

Unfortunately, federal officials chose to fund the cheapest of the three proposals submitted. Factor in the usual graft and corruption that accompanies these types of projects in Mexico and what was finally built was a 10-meter-high sand barrier with a rock surface facing the arroyo, cement was used sparingly in its construction.

The project was completed to great fanfare in 1970 or so.

The bordo provided a sense of security and became the de facto eastern limit of town as the lands right up to it were soon urbanized.

I’m not aware if the bordo was ever put to the test by a hurricane in the few years between its completion and the arrival of Hurricane Liza.

In normal conditions, the waters that run down the arroyo don’t jump the steep sand banks that are characteristic of it through most of its passage east of town, so waters from Cajoncito Arroyo wouldn’t ordinarily have been running along the bordo. But what happened with Liza was that an inordinate amount of water fell over a very short period of time, water which apparently backed up behind the bordo while making its way behind Atravesado Hill to Piojito Arroyo.

Once the section of the bordo gave way, the arroyo reclaimed its old waterways to the sea through the southeastern sector of the city.

It was a “had to be there” moment to fully appreciate what had happened.

Most of the city’s residents didn’t realize the cause of the “explosion” heard that early evening and word didn’t filter back to the rest of the city of the horror that had visited the eastern and southern sections of town until the next morning.

While my family was long gone when Liza devastated La Paz,

I had several friends who were volunteers at the La Paz offices of the Red Cross in 1976. All of them were called in to begin hauling bodies in the pre-dawn hours of Oct. 1st. Initially, the corpses were taken to the Salvatierra Hospital (then on Bravo Street), but as this facility was soon overwhelmed, the dead were taken to the Cancha Manuel Gomez Jimenez on Bravo Street and to the GUM Gym on 5 de Febrero (right on the very edge of the arroyo) and several other locations around town.

The initial idea was to give next-of-kin a chance to claim their relatives.

But as the magnitude of the devastation was realized, government officials decided that the original plan was impractical as bodies quickly began to decompose in the tropical heat. Two backhoes were ordered to the Sanjuanes Cementary where they dug five trenches, each some 70 yards long. The dead were wrapped in make-shift sheets (they bought bolts of cloth from local stores to make them) and dumped one body on top of another in common graves. Six tons of cal (lime) were used to cover the dead to help contain the spread of disease.

It didn’t take more than a few days for public officials to call off the search for bodies, deciding that the arroyo was as good a place as any to be buried. Today one still occasionally hears of a construction site finding human remains in the sections of the city that were flooded.

In doing the research for this essay, I visited the site where the old dike was located, I rode my bike down the arroyo that overflowed with death on that September night and also rode to the top of

Atravesado Hill to survey the area where the nightmare began.

I studied the new fortifications that protect the city from the Cajoncito Arroyo today.

What I found is a bit disconcerting, to say the least. While the north section of the new retaining wall is a beauty with a cement face on the arroyo side, the southern section—the very section that collapsed last time—is (once again) made of dirt/sand with a rock surface facing the arroyo.

Although I’ve never seen a good picture of the old dike, the southern section of the new dike looks a lot like the descriptions I’ve read of the original.

What one also sees are new sections of La Paz growing up in places that have virtually no protection from the arroyo, colonias that will be in grave danger when another Liza hits this area again. If I were shopping for a house in La Paz, I would study where the old arroyos ran, particularly the Arroyo El Palo, which was one of the deadliest arroyos crossing La Paz on the evening of September 30th,

1976. During Liza, sections of Jalisco, Sinaloa, Colima and Colosio Streets were deathtraps for those caught in them.

The new cement “bordo” protecting the downtown area

Although I’ve never seen a good picture of the old dike, the southern section of the new dike looks a lot like the descriptions I’ve read of the original.

What one also sees are new sections of La Paz growing up in places that have virtually no protection from the arroyo, colonias that will be in grave danger when another Liza hits this area again. If I were shopping for a house in La Paz, I would study where the old arroyos ran, particularly the Arroyo El Palo, which was one of the deadliest arroyos crossing La Paz on the evening of September 30th,

1976. During Liza, sections of Jalisco, Sinaloa, Colima and Colosio Streets were deathtraps for those caught in them.

The new cement “bordo” protecting the downtown area

What the bordo protecting the area devastated by Liza looks like

Interesting Tidbits

The literature—as well as my friends’ accounts—mention the suspicion

that the dike was really blown up with explosives by the Army. This theory proposes

that government officials were monitoring the situation and realized that it

wasn’t a matter of “if” but of “when” and “where” the dike was going to give way.

If a section of the dike’s north end gave out, Arroyo El Cajoncito would

have flooded downtown, the city would likely have suffered greater damage

and perhaps more deaths. Under this scenario, public officials would have

coldly decided to sacrifice the sections of the city where immigrants lived to save

the city’s center.

The President of Mexico, Luis Echeverria, visited La Paz on Oct 2nd and

promised the local governor that “whatever you need, just ask and we’ll

send it.” At the time, Echeverria was trying to make Mexico more independent

of US influence and so chose to reject the aid that was collected and offered

by its northern neighbor. Unfortunately, the federal government wasn’t

able to provide what it promised, which left local hospitals in a bit of a jam.

In what sounds like an effort at revisionist history, the governor who

presided during the storm stated in a recent interview that he made the

decision to ignore the presidential order and allowed aid flights in.

One of my Red Cross friends said that only one US Air Force C-130

cargo hauler landed with supplies, which were promptly confiscated by the

military, never to be seen again.

It took eight days for power to be restored to most of the city.

The dam known as La Buena Mujer (The Good Woman) was built as a

response to the devastation caused by Hurricane Liza. It now serves

as a reservoir for the runoff of one of the major arroyos that feed the

waters that run through Arroyo El Cajoncito.

Although it’s narrated in Spanish, you don’t need words to appreciate

the graphic scenes of death and destruction. At around 27 seconds into

the video, during a low-level flyover, one can see the gap in the old dike.

The five trenches where the dead were laid to rest

The marker commemorating them

The gap where all the water came through

The section of La Paz that was wiped off the map

The following story appears online in Spanish. It is an account written

(or, more likely, narrated into a recording device) about one person’s

experience during Liza and is quite moving. In its original form, it is one

very long story that makes little or no use of punctuations, paragraphs

or any of the other norms of writing. In my translation, I have taken

the liberty to break it up into more readable blocks of information

and omitted some passages that were repetitive or didn’t add to the

storyline. The original story, with many photos of the devastation

caused by Hurricane Liza, can be found at:

http://navegantecalifonio2008.blogspot.com/2008/09/yo-sobrevivi-al-ciclon-liza-1976.html

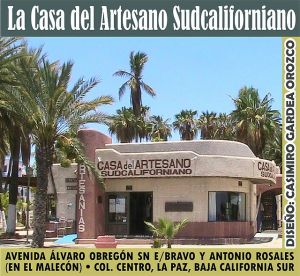

I SURVIVED CICLON LIZA 1976

By Casimiro Gardea Orozco

My story begins on September 30 of 1976. I remember getting up early to go

to work with my stepfather, with whom I was working practically since I arrived

in this city. I’d arrived in La Paz in August of 1975 onboard the Salvatierra,

the ship that later sank in front of Espiritu Santo Island.

I remember on that fateful day my stepfather and I went to finish plastering

some commercial locations we’d built for a man over in front of the military

base. We were getting close to finishing the job when my stepfather told

me and another guy who worked for him—I think his name was Valentin—that

the owner said we should knock off for the day and go home because

the hurricane was going to hit the city, so we cleaned and stowed our tools.

By then I think it was about 10:30 a.m., we finished up and bid each

other goodbye. My stepfather left on his bicycle while I headed

home on foot. I hadn’t walked five blocks when it began raining,

so I hurried home, where I arrived soaking wet. Without changing

clothes, I announced my arrival to my mother as she attended to

my youngest brother and told her that the hurricane was about to

arrive. I began to cover the windows and door of the house

the best I could, nailing a thick blanket to the door and putting

cement blocks along its bottom to help support it against the

strong winds that had begun to blow. I had to restack the blocks

every so often after the winds would push them over.

At around 3 or 4 in the afternoon a calm arrived over the city, which allowed

me to go outside to check on things in our yard. As I was doing this my

stepfather, also taking advantage of the calm, arrived in a station wagon

to take us to the military base which was being used as a refugee center.

But it soon began to rain and the winds returned stronger than ever.

Taking only our blankets, we piled into the wagon and began driving

down streets that had become flooded arroyos, seeking a way to our

destination. The rain was so heavy that at times we couldn’t even

see where we were going. We got stuck numerous times but managed

to continue on, until the roof of a house fell in front of the vehicle and

we decided that it would be better to return home. As we headed

back we got stuck in the mud repeatedly and our vehicle took several

hits from airborne debris. Several times we had to practically carry the

vehicle out of the rain-swollen arroyos, which seemed to get deeper

with each passing moment.

After a two-hour struggle, at around 6 p.m. we finally made it back

to our home. Before we got out of the vehicle my mother’s compadre

came up to invite us to wait out the storm at his house, which was

made of cement block and also had a cement roof (Tripper note:

this passage indicates that the family lived in a house made of materials

that were temporary in nature, a practice common in Third World

countries). It seemed like a safe place for us and the other four families

already there to take refuge. As we settled in, drank coffee and chatted

we all felt comfortable and safe, the mood was light-hearted as we thought

the worse part of this experience was behind us. We talked about the places

we were from. We had all come from other parts of the country to seek work

in La Paz because we thought it was like going to the United States to earn

dollars since it was in the zona fronteriza (border zone) and there was

a lot of tourism and we thought everything was paid for in dollars.

After about three hours of this enjoyable banter we heard a sound

very different from the noise of the wind and rain that had been

plummeting the roof and walls that surrounded us. It was a

deafening sound accompanied by a small tremor that seemed to get

nearer and nearer to us. A young guy about my age who had

been visiting decided that it was time for him to return to his home.

He left, but soon returned because the currents in the arroyo were

too strong to cross. By then water was intruding under the doors

in spite of the blankets that had been placed under them to prevent

such leakage. That was when we heard one of the walls of an

adjacent empty room in the house collapse. This was followed

by the sound of rushing water hitting the walls of the room we

had just vacated.

We realized that soon the whole house would be brought down

by the force of the water rushing by. My mother’s compadre said

we should leave the house and climb aboard the motorhome

parked outside the residence, which we all did. Wood and other

building materials from houses the waters had already destroyed

piled up in front of the property we were at, parting the waters

and forming an island that gave us sanctuary. But then we began

to feel the impact of the material from the house we had just

vacated as it began hitting the undercarriage of the motorhome we were in.

One of the men in our group said he heard a child crying under the

motorhome and so he and my stepfather went outside to search for him.

That was when the last standing wall of the house we’d been in gave way,

falling into the motorhome and knocking it over onto the man my stepfather

had accompanied outside, killing him. Logically, we assumed my stepfather

had suffered the same fate.

But luck was with him. He recounted several days later that when the

motorhome fell over, it created a huge splash which lifted him up into

the arms of a large cardon cactus that was in front of us. He spent

several hours up in the cactus, until the waters running in the arroyo

were low enough for rescuers to arrive and help him get down.

He showed me the many thorns still embedded in his body,

which doctors had decided to leave in place until his body expelled

them naturally. From his perch that night, my stepfather had to watch

helplessly as his entire family was swept away, one by one,

by the raging currents of the arroyo.

When the motorhome turned over, the first thing we did was pray to God

and then decided that it would be best to get out of the vehicle and try to

reach the roof. We got the women and children out first. But no sooner

did we get a person out that the raging waters would sweep them away

because there wasn’t anything to hold onto. Eventually, only the other

kid my age and I were left on top of the vehicle. Although it was dark,

there was a visibility akin to a moon-lit night which allowed us

to see our surroundings in a limited way. It seemed like we were in the

ocean, for water was all around us as far as one could see. The two

of us were in that situation for about twenty minutes when we felt the

vehicle begin to float under us.

That was when I heard a baby cry out. I was able to spot him floating

on some wood nearby. The humanity in me drove me to leave the

relative safety of the motorhome “island” and try to rescue this

fellow human being. But before climbing off the motorhome I told the

other kid that he should grab a piece of wood from the debris to use

as a flotation device, just in case. I don’t know if he understood me,

but when he didn’t react, I grabbed one myself and handed it to him

before setting off to rescue the baby. As I crossed over wood and

other debris, I could tell everything was floating, for it felt as if I were

jumping on a couch. When I reached the baby, I realized he was

my younger brother. I took him in my arms and started back for

the motorhome. With the other guy’s help, I was beginning to climb

back aboard when a large wave knocked me off balance and

swept my baby brother and the other guy into the river below.

Once I climbed back onto the motorhome, I felt very alone, but soon

another wave hit me. I felt the skin of my fingertips get torn away as

I tried in vain to hold onto the vehicle. Then I, too, was swept

downstream. At times I was dunked underwater before popping

up again to catch my breath before being dunked once more

as I was pushed along by the rushing waters. I don’t know how,

but I was able to grab a hold of a large piece of wood floating near

me. With the wood’s buoyancy, I was able to minimize the dunkings

I had been subjected to before.

As I was being rushed along, more than once I was able to make

out upcoming fence posts that had barbed wire between them.

I knew the grave danger these posts represented, so when I couldn’t

avoid them, I tried to get my body as horizontally as possible so

as to pass between the strands of wires like a board. I had to do this

maneuver several times during my journey down the flooded arroyo.

At one point, I could make out the posts of high tension wires and tried

to navigate myself over to one of them to try to latch on, but to no avail.

A pocket of air formed in front of the cement base that wouldn’t allow me

to even slam into them. At times I lost my grip on the wood I was using for

flotation and was at the mercy of the currents. I could feel large rocks being

swept along underneath me, just brushing against my legs but never doing

me any harm, thank God.

At times during my journey, the water became shallow and I was able to

stand up, only to be knocked down once again when the rushing water

flushed the sand out from under my feet. I tried standing up several times

but was never able to stand for long, so I quit trying, letting the water hit

my back in full and rush me past large distances until I was in deep water

again. In deep water my main concern was staying afloat and keeping

my head above water.

As I was floating along, I suddenly heard another sound the water

was making, which I recognized as the sound of an upcoming

waterfall like the ones I’d known back home in Chihuahua.

Just as I knew to avoid the barbed wire fences because I’d seen

how they could kill cattle caught in them when arroyos occasionally

flooded back home, I also knew the danger waterfalls represent.

One could be knocked unconscious or break bones during a fall and

that was my immediate fear. But there wasn’t anything I could do but

resign myself to my fate and try to brace myself mentally for what

was to come next. Just as I was being swept over the fall,

I suddenly felt my progress halt and felt the full force of the rushing

water engulf me. I struggled to get my head out of it to breath.

My legs were pinned down by the water’s force as I continued

my struggle for air. At some point, I realized that what was left

of my pants had been caught by the roots of a small tree that

was also struggling for survival against the water’s rage.

I don’t know how, but I somehow managed against all odds to grab

the trunk of the tree and was able to briefly stand on the arroyo

bottom. But I realized that this action was causing the soil holding

the small tree in place to be washed away, so I let the water take

me horizontally again while I held onto the tree. I was in this

position for some time, watching helplessly as other people were

swept pass me and over the waterfall, a fate I should have

shared with them. Sometimes, I could see them stretch out their

arms towards me for help, but there was nothing I could do for

them under those circumstances since they were out of reach

and I was up to my chest in the water and unable to move.

I remember gradually distinguishing sounds other than the raging

waters and suddenly realizing that someone was yelling at me from

the houses of INFONAVIT and telling me to hang on just a bit longer

while they helped me (Tripper’s note: INFONAVIT is just north

of Soriana’s on Forjadores Street and is one of the colonias that

was hit hard by Liza’s floodwaters). I looked around for where the calls

of help were coming from specifically and saw a person who was using

a flashlight to light the area around me. I thought that he must be yelling

at me and that was when I reacted, asking for his help. But I don’t think

he heard me since he was flashing his light on a large wall that was in front

of me just after Forjadores Street. I could see a lot of people sheltered

in a building with white walls and could make out the silhouettes of other

people who went back and forth but couldn’t leave their location

because the water was rushing past them on either side.

My would-be rescuer came towards me and I heard him, clearer than before,

say that he was coming for me, but I didn’t see him get any closer to me.

Then I suddenly heard someone about 30 meters away from me say he was

going to help me and that I needed to hang in there just a little longer.

That was when I finally saw a silhouette nearing me, holding onto what

appeared to be a slide or some other type of playground equipment until

he could reach me with his extended arm and tell me to grab a hold of it

and not let go. And that is just what I did. I let go of the little tree’s trunk

as he pulled me out of the arroyo and then he backed up and told me to

follow in his footsteps until we reached the sidewalk in front of colonia

INFONAVIT where there is now a rock wall.

We began walking towards Sinaloa Street. When we reached Jalisco

Street, I remember seeing a man inside one of those cages that use

to protect water mains. We told him to get out from the cage and come

with us because he’d surely drown in there if the water level rose again.

But he refused to listen to us and instead went further into the cage.

We continued walking until we reached the old road heading south,

walking along a long line of cars that had been trapped between

Sinaloa and Colima Streets. Everyone looked at us with shocked

expressions on their faces, but nobody came near us or talked to us.

Seeing us in rags, seminude and full of mud, they simply got out

of our way. Perhaps we were the first people they had seen that

managed to get out of the raging floodwaters . Perhaps they didn’t

find out until the next day of the magnitude of the tragedy that the

city of La Paz was living through. Perhaps at that very moment lots

of people were still floating, dead or alive, in the bay of La Paz.

We walked until we reached the corner of Sinaloa Street and Forjadores,

were we attempted to cross the street but failed because the current

was too strong so we sat down with our backs to a wall to wait for the

waters to recede. We sat there, resting for a while when a woman from

a house that still exists to this day invited us in to her home

(Tripper note: a business has replaced this house). She said there

were lots of people in the house already, but that we could stay in one

of the cars in her yard and she then opened the door to one of them.

She left to prepare us a cup of hot tea. Once inside the car, the interior

light came on and that was when I realized that the guy who had helped

me was the same one who was in the house with us earlier that evening.

But we hadn’t spoken since he’d told me to follow in his footsteps after

pulling out of the water. I also noticed how he rubbed his right hand and

how his little finger was suspended from his hand by a thin piece of tissue,

which he apparently hadn’t noticed until that moment.

When the woman returned with our tea I asked her for some scissors.

Without asking a thing, she left and returned with them. I used them

to cut the tissue still attaching his finger to his hand and wrapped

it in a neckerchief I found on the car’s seat and put it in his hand.

He held onto it tightly as I drifted off to sleep. When I awoke, he was no

longer in the car. I, too, left the car. Sinaloa Street was now empty

of water. I walked about two blocks and could still hear water rushing

down other arroyos. Suddenly, some soldiers appeared out of nowhere

and asked me what I was doing there and said it was very dangerous

there because of the arroyo. I told them I’d escaped from the arroyo and that

was when I saw the first dead people among the piles of debris of boards,

wood, tree branches, furniture and everything else that was along the

arroyo bank. Some corpses had arms or legs jutting out from the piles

while one could see the backside of others as their heads and legs were

buried under piles of trash. The soldiers were picking up some of the bodies,

those with uniforms. It seemed like they were only separating their own

from the debris.

One of the soldiers took me to the soldier in charge of the scene and told

him I’d managed to escape from the torrential waters. The man in charge

told my escort to take me in a jeep over to a school that was being used

as a refugee center, which he did. I don’t remember which school he took

me to, but what I do remember was that as we transited the streets sometimes

the water was deep enough to almost cover the jeep’s tires.

When we arrived at the school, the soldier told the person he turned me

over to not to let me out of his sight, and he didn’t. I was brought a blanket

and taken to a classroom where I looked out a window and saw how the

water was still rushing with considerable force by the side of the building.

I fell asleep again. Around dawn someone woke me up and asked if I was injured.

I showed him my hands and he told me to get aboard a truck that would take

us to the hospital to be checked out. Some of the others on the truck had

large head injuries while others had injuries on their legs and arms and still

others were unconscious.

After we arrived at the hospital it was several hours before a doctor asked

what was wrong with me. I told him the skin on my fingers was peeled off and

I had been hit in the stomach. He checked me out and said nothing was

wrong with me but washed my hands with oxygenated water and said he’d get

me some clothes. When he returned with a pair of pants and a shirt, I put them

on right then and there and left the hospital, heading up Nicolas Bravo

Street (Tripper note: this is the street the old Salvatierra Hospital is on).

As I neared the area affected by the storm I began to appreciate the

enormity of what the flood waters had done. When I arrived at the

arroyo there wasn’t any more water in it. In fact, it looked as if it had never

had any water in it at all. Sections of it were so clean that they looked as if

they’d been swept. The sand was so white that the sun’s reflection

off of it strained my eyes. I began to see the half-buried bodies once

more and a lot of people looking for bodies and marking the spots were they

found them. Pickup trucks passed by full of corpses covered with dirt and mud.

I continued to walk towards our house. When I arrived I was surprised to

find everything was as we had left it. The blanket was still in place on the door

and the water level inside the house had only risen to about a foot. In fact,

it hadn’t even reached the mattress on the bed. I sat down to contemplate

what had happened when my older brother arrived and asked me about the

rest of our family. I told him the flood waters had taken them all and we

cried together.

Once we calmed down we decided to go look for them. We looked in

a lot of places but never found anyone until we arrived at some soccer

fields on Allende Street. We watched as workers were washing off corpses

with a hose to clean them up so their family members might be able to

recognize them. That was where we found first, our six-year-old brother

and then, inside of the building, we found our mother—still holding our baby

brother in her arms. Somehow, when the baby slipped out of my grasp,

she was able to recover him while they floated downstream, never letting

go of him, not even in death. We never found my sister.

Another younger brother of mine was rescued by soldiers from the roof of a

house under construction near the Hotel Gran Baja (Tripper note: this hotel,

now empty, is on the shore of the Bay of La Paz and should have had

guests when Liza struck). He’d been washed down the arroyo and would

have likely drowned in the bay if not for a large nail that pierced through

his foot and anchored him to the structure, keeping him from being

swept to sea. He required over a year of medical treatment and

therapy to recover from his injuries.

After this tragedy, my older brother suggested that the three of us should

intern ourselves into the Ciudad de los Niños (Tripper note:

the Ciudad de los Niños [City of the Children] is a local orphanage

and is located next door to the Santuario [huge church] on

Cinco de Febrero), where I became a trainee in the printing shop.

The rest of the story talks about how he eventually learned

the Graphic Designer trade at the orphanage and still works in the trade today.

The End

Where the house he was swept from was once located,

note the arroyo on the right.

Where he was pulled to safety, next to present-day Burger King Restaurant

The area he traveled down the arroyo

The area his brother traveled before finally getting “nailed” to a building under construction

We drove down in December 1976 and were amazed at how the

landscape around La Paz had changed from the effects of the

hurricane-everything super green. Here is a photo taken

in front of Martin Verdugo’s Trailer Park- not much sand but lots

of wood that got washed out from the desert and then packed

onto the beach. Martin Verdugo told us that the water was waist

to chest high and they had to hold their children up above the water

for a long time so they didn’t drown.

An interesting aside on the ending of the Salvatierra is related to

Hurricane Liza.

Either the Ruffo’s (the ship’s owners) or their insurance carrier contracted

an American salvage company to come down and refloat the ship.

The process was well underway–they’d brought with them sacks to inflate